Shellfish Harvest Opportunities

Shellfish Harvest Opportunities

What percentage of our estuaries are open for shellfish harvesting and how has this changed over time?

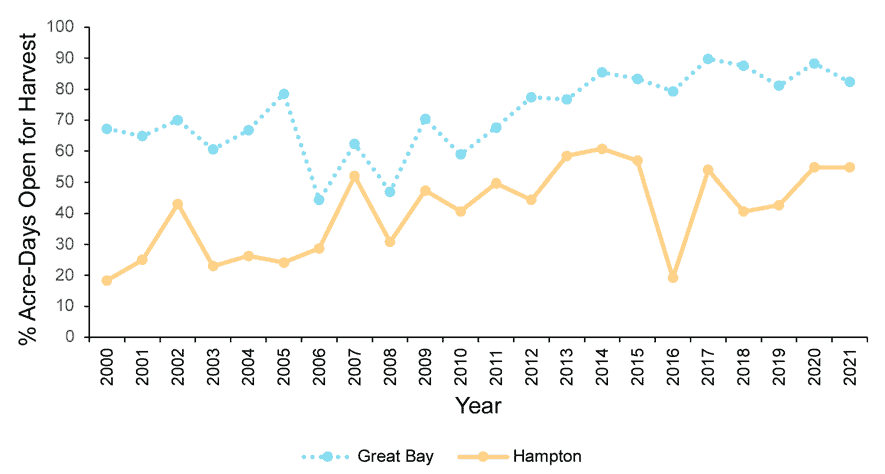

The percentage of possible acre-days when shellfish beds are open has been on a statistically significant, gradual upward trend from 2006 to 2021 . Factors driving the upward trend in harvest opportunities in our estuaries include wastewater treatment facility upgrades, the opening of new harvest areas in Little Bay and the Oyster River due to expanded testing programs, better understanding of pollution dispersion by tidal currents, and improved management of risk related to potential boat sewage contamination . Increased harvest opportunities coincide with decreasing bacteria concentrations (see “Bacteria”), underscoring the effectiveness of management efforts.

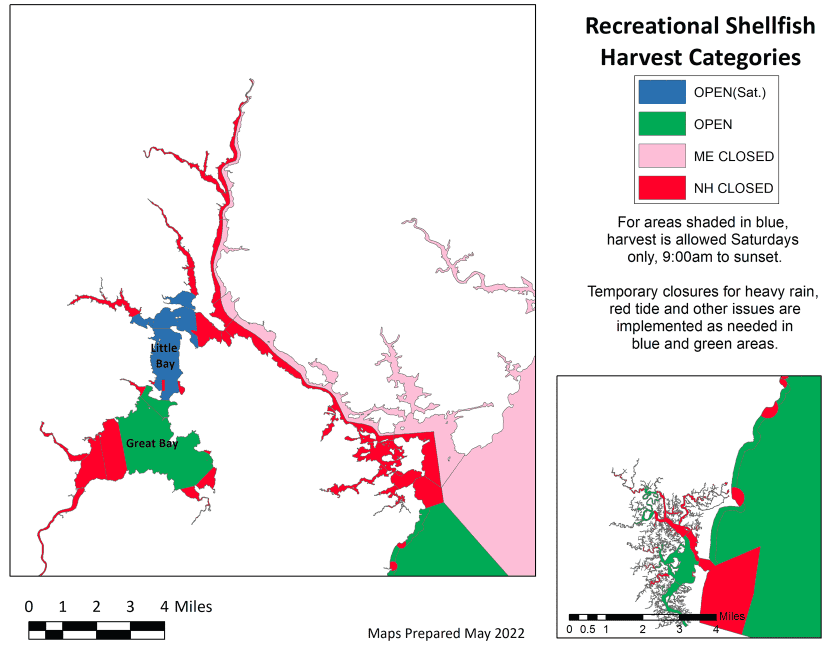

Figure 16.1 indicates open and closed areas of the Great Bay and Hampton-Seabrook Estuaries for shellfish harvesting in 2021. The percentage of possible acre-days (i.e., the number of open acres multiplied by the number of days those acres were open for harvest) in 2021 was 82% for the Great Bay Estuary and 55% for the Hampton-Seabrook Estuary (Figure 16.2).

Shellfish areas often are closed as a safety measure, especially after heavy rainfall, because significant rain events often lead to increased pollution. In addition, operational problems, either at wastewater treatment facilities or in the sewer infrastructure, can lead to closures because of improper discharge of treated sewage. To re-open a shellfish area in these instances, New Hampshire Shellfish Program staff analyze water samples to ensure the number of fecal coliform bacteria meet established safety standards (see “Bacteria”). Samples of shellfish tissue also are analyzed for certain types of pollution events.

Less often, areas are closed due to the occurrence of harmful algae blooms, commonly known as “red tide.” Since 2000, red tides have been responsible for multiple day closures in nine different years. In some years, red tides may have occurred at times when the beds were already closed for conservation purposes; in those cases, they are not recorded as contributing to more closures.

Much of the Great Bay Estuary and Hampton-Seabrook Estuary data reflects the interannual variability of weather, with wet years leading to more numerous temporary harvest closures. The large number of closures in 2016 in the Hampton-Seabrook Estuary was the result of a significant discharge of raw sewage from a broken 14-inch sewer pipe under a salt marsh in the Town of Hampton. The long-term trend of gradual improvements since 2000 might reflect improved data collection and pollution source management by New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and seacoast municipalities. Such efforts include programs to identify and eliminate illicit discharges, upgrade or build new wastewater treatment facilities, reduce wet-weather “combined sewer overflows” by expanding and upgrading sewer collection lines and pump-station capacity, and develop a more detailed understanding of individual wastewater treatment facility operations, effluent quality, and distribution patterns of pollutants in the receiving waters.

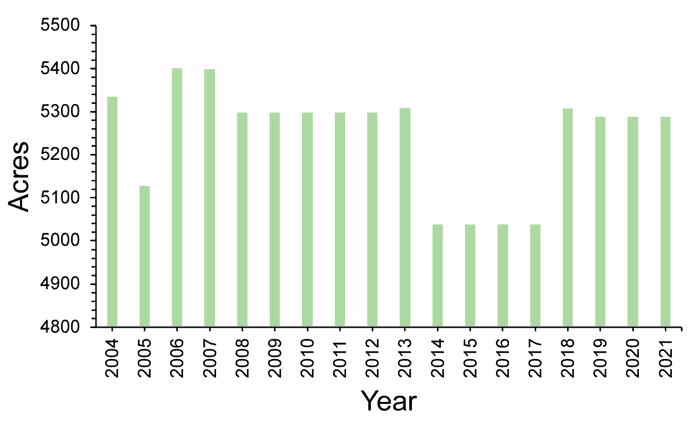

The amount of area designated as conditionally approved — open but subject to temporary closures due to water quality issues — has remained relatively steady at around 5,300 acres in recent years (Figure 16.3). The drop in acres during 2014 – 2017 was based on results of the December 2012 Portsmouth Wastewater Treatment Facility Dye Study, which examined how the former treatment facility affected water quality in the estuary.49 The earlier version of the facility employed a relatively simple sewage treatment process. At a total cost of over $90 million, the new facility uses more modern sewage treatment technologies and treatment, resulting in more thoroughly treated effluent. Subsequent studies of effluent quality and seawater/shellfish microbiological indicators have allowed for some of the previous harvesting restrictions to be relaxed. In addition to the Portsmouth improvements, Exeter upgraded its wastewater treatment facility and significantly upgraded its sewage collection system — completed in 2020 at a total cost of $53.5 million. As post-upgrade monitoring of water quality continues, shellfishing areas might be opened more frequently.

For the Hampton-Seabrook area, most of the closed areas (red areas in Figure 16.1) are safety closures due to the proximity to the outfalls for the Hampton and Seabrook Wastewater Treatment Facilities. The Town of Hampton facility relates to the red area within Hampton Harbor and the Town of Seabrook facility relates to the area in the Atlantic Ocean, offshore of Seabrook Beach. The Seabrook facility releases its effluent 1,500 feet offshore via an underground pipe. Both facilities are modern systems that are functioning effectively with regard to effluent disinfection. However, the New Hampshire Shellfish Program maintains safety closures due to the contingency of a temporary system breakdown.

The two smaller red areas in Hampton and North Hampton are related to unexplained but occasional occurrences of very high fecal coliform bacteria, possibly caused by owners not picking up pet waste.

Maine waters, including areas of the Piscataqua River and Spruce Creek, are closed for harvest, partly due to concerns about the Portsmouth facility. The exception to this is Spinney Creek Shellfish in Eliot, Maine, which has a specialized facility for removing potential pathogens from shellfish. As ongoing studies document the positive water quality effects of the Portsmouth facility upgrade, the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services and Maine Department of Marine Resources will reassess the public health risks and modify harvesting classifications in the areas under their jurisdictions.

Acknowledgments and Credit

Chris Nash (NH Department of Environmental Services, Shellfish Program)

Figure 16.1: Map showing recreational shellfish harvest categories for both the Great Bay and Hampton-Seabrook Estuaries. Data source: NH Department of Environmental Services, Shellfish Program

Figure 16.2: Shellfish harvest opportunities for Great Bay and Hampton-Seabrook Estuaries. Graph displays percentage maximum possible “acre-days,” which is the number of open acres multiplied by the number of days those acres were open for harvest. Data source: NH Department of Environmental Services, Shellfish Program