Oysters

Oysters

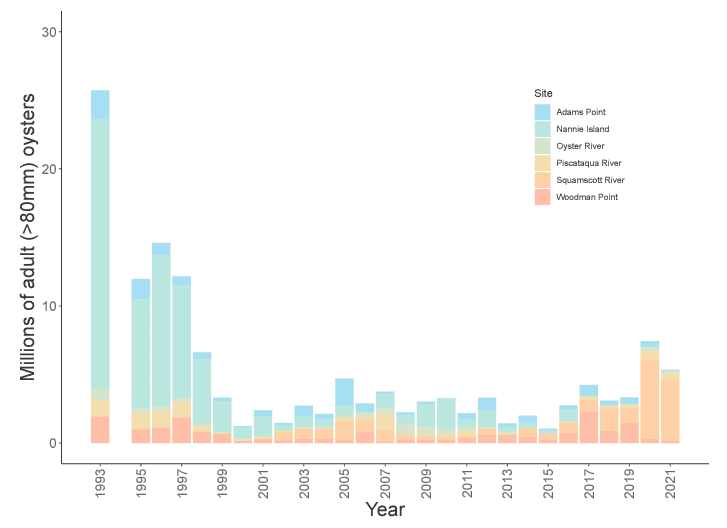

How many adult oysters are present on natural reefs in the Great Bay Estuary and how has the number changed over time?

The number of adult native oysters (Crassostrea virginica, the eastern or American oyster) decreased from >25 million in 1993 to ~1 .2 million in 2000, a 95% loss (Figure 17 .1). Annual sampling since 2000 had indicated <5 million were present each year until 2020 when oysters rebounded to 7 .4 million on natural reefs. Additionally, oyster aquaculture has dramatically increased in the past several years and in 2021 there were nearly as many live oysters on aquaculture facilities as adult oysters on the natural reefs (see below).

Wild oysters mainly occur on subtidal reefs in the Great Bay Estuary but have been found in intertidal waters in recent years. The six major subtidal reefs are monitored annually providing abundant data for long-term assessments. Underwater video surveys in 2020 by UNH scientists indicated that the total area covered by live reefs was ~80 acres,51 compared to historical (1970s) estimates of “live oyster bottom” coverage ranging from 900 to 1,300 acres.52

A major limitation on oyster health for the past 20 years has been disease caused by two microscopic parasitic organisms: Dermo (Perkinsus marinus) and MSX (Haplosporidium nelsoni). Both parasites are present in both wild and aquacultured oysters in the Great Bay Estuary.53 Whereas MSX is in decline in the Estuary, Dermo, a warmer water parasite, has become more prevalent in the last decade, and is expected to be favored by warmer winters as climate change continues.54,55 In recent years, oysters have rarely grown past 115 mm in shell height. This suggests average longevity is now only 4 or 5 years rather than 10+ years as in the early 1990s, when oysters greater than 200 mm were common.

Oyster populations in the Great Bay Estuary also face challenges due to a lack of suitable substrate on which oyster larvae can settle. Oysters themselves provide hard substrate as they grow and increase in shell size, but less and less oyster habitat diminishes the available hard substrate for new recruits. This has been offset to some extent by deploying oyster and other mollusk shell — from restaurants and other sources — in key locations in the Great Bay Estuary (see “Oyster Restoration”).

Sedimentation is another stressor related to the issue of available substrate for new oysters to set. Sediments enter the estuary from run-off, eroding salt marshes and stream banks, and can be resuspended from the bottom sediments during storm events. With eelgrass and oyster habitats decreased from historic levels, sediments may be more easily resuspended following storms and high-flow periods. Oyster restoration monitoring has indicated that young reefs can be rapidly smothered by sediment in many areas.

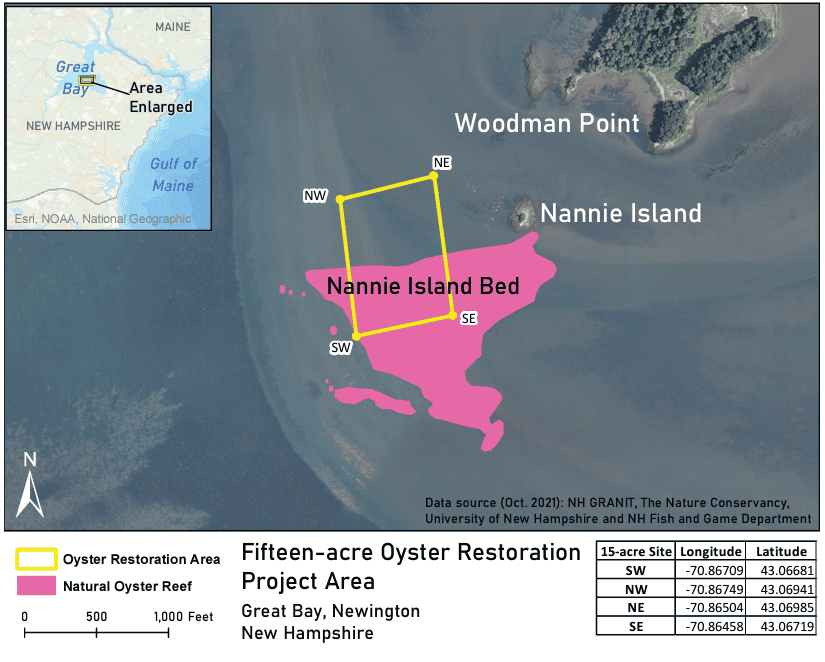

Recreational harvesting of oysters also may be stressing the population. Although studies from other areas have shown that restricted harvesting can provide benefits through the resuspension and removal of sediment on reefs that are regularly harvested, there are no data that quantify the relationship between oyster harvest and sediment removal. In reaction to the Nannie Island oyster reef population decline (shown in Figure 17.1), the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department implemented a five-year harvest closure (2022 – 2026) of a 15-acre area covering a substantial portion of the Nannie Island oyster reef to encourage oyster growth and provide an opportunity for new restoration projects (Figure 17.2; see more discussion in “Oyster Restoration”).

In the past 10 or so years, eastern oysters have been documented in the intertidal zone in New Hampshire and Maine, and anecdotal evidence indicates this is a recent phenomenon likely related to climate change.56 Rock outcrops and other hard substrata in the intertidal zone of the Great Bay Estuary are typically covered by two fucoid brown seaweeds: Ascophyllum nodosum and Fucus spp., collectively called rockweed. Oysters in the intertidal zone of the Great Bay Estuary only occur under the rockweed canopy. These intertidal oysters have not been quantified, but available data indicate the total intertidal population could be as much as the subtidal reef population.

Acknowledgments and Credit

Ray Grizzle (UNH), Krystin Ward (UNH), and Robert Atwood (NHFG).