Oyster Restoration

Oyster Restoration

How many acres of oyster reef restoration projects have been initiated since 2000?

Although there are insufficient data to fully evaluate the PREP goal, oyster reef restoration projects totaling about 75 acres have been initiated since 2000. Sedimentation and other mortality factors hampered success at most sites, but methods have been developed recently that show good promise. Moreover, the process has become highly collaborative in recent years . Planned projects for 2023 and future years involve collaborations between New Hampshire Fish and Game Department, The Nature Conservancy, the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, and the University of New Hampshire. Restoration projects are focused on the Great Bay Estuary since there is no historical record of oysters in the Hampton-Seabrook Estuary.

There is no widely accepted method for determining when an oyster reef has been “restored.” Current research includes efforts to determine metrics that will allow assessment of this goal.

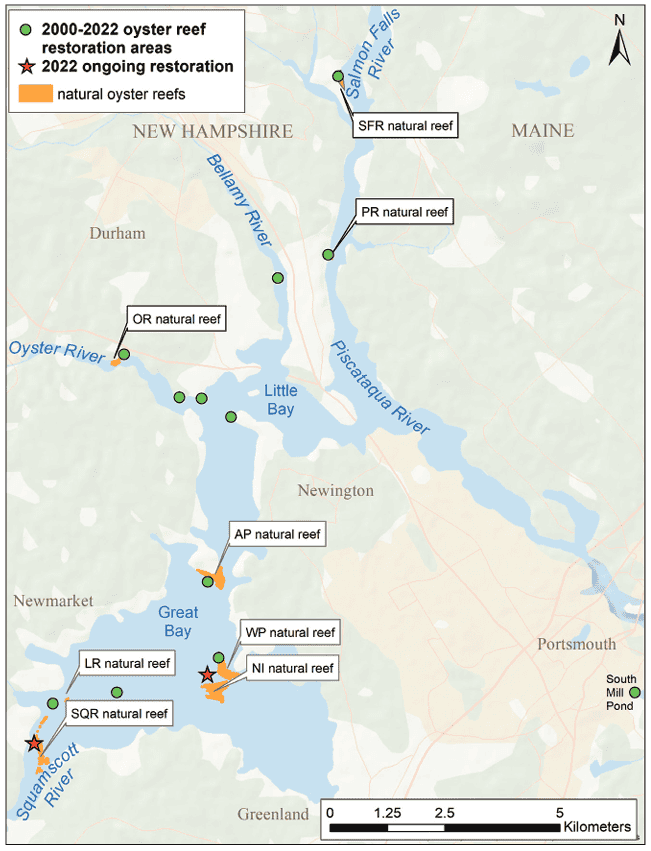

Between 2000 and 2021, 75 acres of oyster reef restoration projects were initiated (Figure 17.3), but the success of most projects was not quantified beyond one or two years. Recent assessments of restoration sites up to 13 years post-construction indicated most sites had a reduction in base shell cover compared to initial restored reef base, and constructed reefs located near native reefs had the highest live oyster densities.57 However, there are insufficient data on live oyster density, recruitment to the area (new oyster larvae settling), and reef areal coverage at most sites to allow a current quantitative assessment of “restored” reefs.

Disease, lack of hard substrate, and sedimentation explain the major constraints on reef restoration. Long-term development of the constructed reef is largely dependent on two factors: the shell base remaining above the soft sediment surface so that oyster larvae can settle, and an adequate level of natural recruitment from wild oyster larvae. Unfortunately, the recent longterm assessments discussed above found substantial losses (burial and/or subsidence) of the shell base at many sites and lack of natural recruitment at most. These findings resulted in two new design criteria for most projects since ~2018.

First, reef restoration sites are positioned as close as possible to a natural reef, since recent research showed that recruitment decreased significantly as distance from a native natural reef increased.58 Second, reef bases are designed to consist of multiple mounds of mollusk shell projecting less than 0.5 m above the sediment surface and arranged randomly across as much of the restoration site as funds will allow (typically ~25% coverage).

Acknowledgments and Credit

Ray Grizzle (UNH), Krystin Ward (UNH), and Robert Atwood (NHFG).

Figure 17.3: Locations of major oyster restoration projects (green dots) since 2000 and remaining natural oyster reefs (orange polygons). Note that there were multiple projects in five of the areas in the Squamscott River (SQR) and Lamprey River (LR), Adams Point (AP), and near Nannie Island (NI). Also shown are Woodman Point (WP), Oyster River (OR), and Salmon Falls River (SFR). Data source: University of New Hampshire

Although oyster aquaculture is usually thought of in terms of economic metrics and currently there are no management goals, this activity is directly related to oyster abundance and oyster restoration goals.

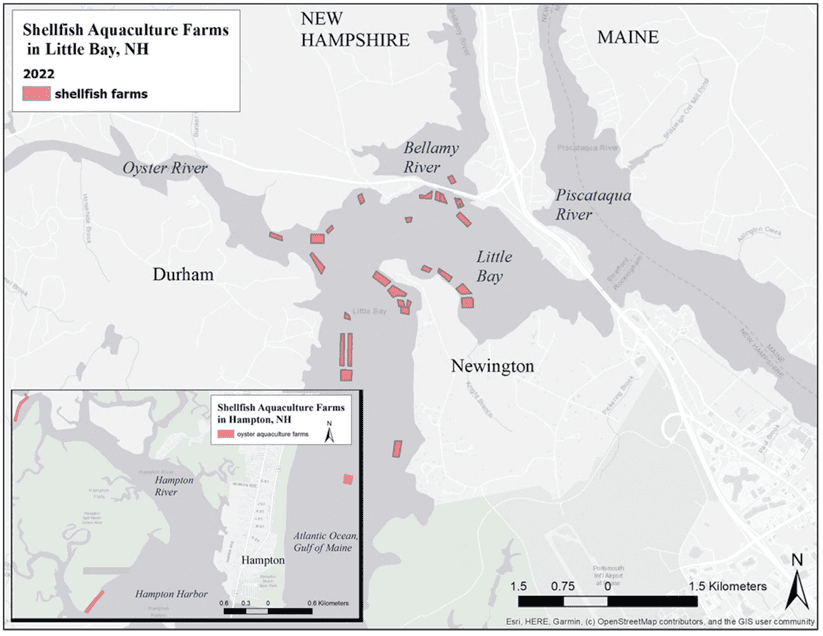

Shellfish aquaculture (primarily eastern oysters) in New Hampshire has grown from six acres in 2010 (two businesses) to 80.4 acres in 2021 (16 businesses; Figure 17.4). The average annual oyster harvest was 581,749 for the past five years (2017 to 2021), a dramatic increase from 2012 – 2016 when the average harvest was 129,045 oysters. Nearly a million oysters were harvested from New Hampshire’s oyster farms in 2021, including ~30% sold for use on oyster restoration sites (see “Oyster Restoration”). Oyster aquaculture in New Hampshire is an economically and ecologically important industry that is rapidly growing.

In 2021, there were ~7 million oysters (20 – 100 mm shell height) on 74 acres of licensed aquaculture sites in Little Bay — roughly the same number as the ~7.4 million adult (greater than 80 mm) oysters on natural reefs in 2020. Although not directly comparable, the numbers clearly indicate that the total population of farmed oysters (all size classes) is similar to that for adult oysters on natural reefs in recent years. Additionally, if farmed oysters and wild oysters were counted in the context of the aforementioned goal of 10 million adult oysters in the Great Bay Estuary by 2030, then that goal may have been met in 2021.

Four key facts explain how farmed oysters are important to PREP’s goal of more abundant wild oysters. First, farmed oysters in New Hampshire are from “seed” (juvenile oysters) produced by brood stock maintained in hatcheries, mostly in Maine. In other words, they are not from wild New Hampshire or Maine oysters. The brood stock oysters in most cases have been selected for fast growth and disease tolerance. Recent data have indicated that farmed oysters >3 years old have less disease and they generally are larger in size than wild oysters of similar age. Second, although there are important differences, oysters on farms do provide water filtration. Third, oyster farms also provide habitat for a wide range of organisms. Recent research in the Great Bay Estuary found that farm gear supported invertebrate and macroalgal communities similar to adjacent eelgrass and oyster reef habitats.59,60 Fourth, the larvae produced by oysters on farms can disperse away from the farm sites and may produce recruits for wild reefs.