Diadromous fish are those that migrate between freshwater and marine ecosystems to complete their life cycles. These fish require estuarine habitat that effectively links coastal ecosystems to bays and their freshwater tributaries. Across North America, diadromous fish have experienced dramatic population declines over the past century due in part to dams, overfishing, loss of habitat resulting from coastal development, and decreases in water quality.

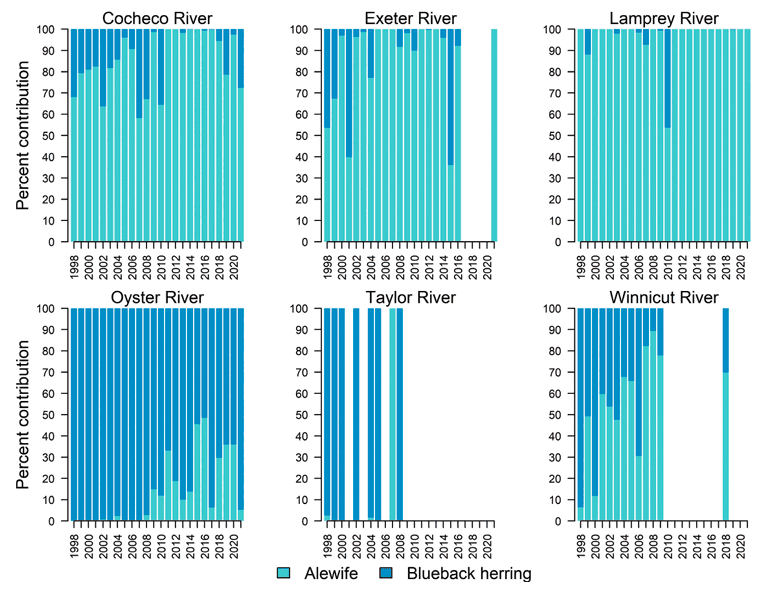

In the Gulf of Maine, migratory species that use the Hampton-Seabrook and Great Bay Estuaries, such as river herring, have similarly experienced declines. The term “river herring” is actually a common name that refers to two different species: blueback herring (Clupea aestivalis) and alewife (Clupea pseudoharengus). Since 2008, the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department has estimated the numbers of each species returning to each river. Most tributaries of the Great Bay are dominated by one species or the other. For example, most river herring returning to the Cocheco River, Exeter River, and Lamprey River are alewife (Figure 20.1). In contrast, most river herring returning to the Oyster River are blueback herring, but the relative contribution of alewife to this river has increased over the past decade.

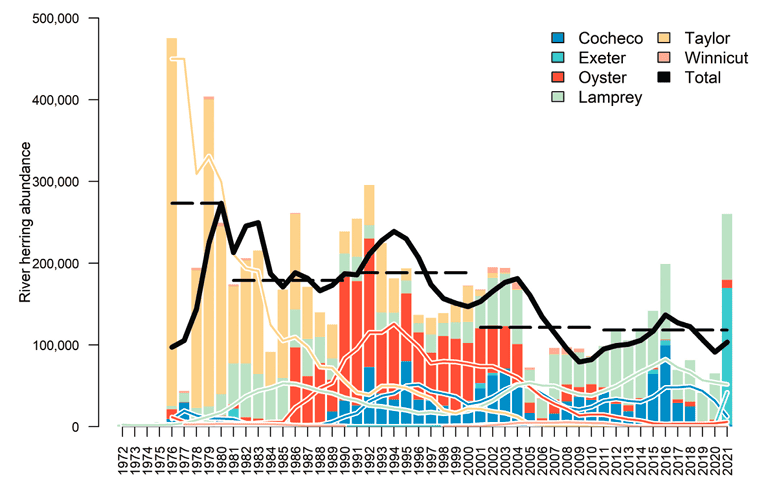

Observed river herring returns to the coastal rivers of the Piscataqua Region Watershed varied during the 1972 – 2021 period (Figure 20.2). From ~1975 – 1985, returns were dominated by the Taylor River and, to a lesser degree, the Lamprey River.

From the mid-1980s to the early 2000s, returns on the Oyster River and Cocheco River dominated total returns. In the early 2000s, the Taylor River run collapsed and returns to the Oyster River dropped considerably, leaving returns to be driven by the Lamprey River and Cocheco River through 2020. Total river herring returning in 2021 reached 260,065 (30.6% increase from 2016), but this was driven by the highest returns recorded on the Exeter River (167,400); note that the Exeter River is the freshwater portion of the Squamscott River. This increase was likely in response to the removal of the Great Dam in 2016.

Fewer than 10 fish were reported for the Taylor and Winnicut Rivers in 2021, and returns have decreased in the Oyster River over the past ~20 years. Overall, the mean annual river herring returns among all monitored rivers over the past two decades (118,222 in 2011 – 2021 and 121,590 in 2001 – 2010), are lower than those observed in the 1980s (179,076) and 1990s (188,386).

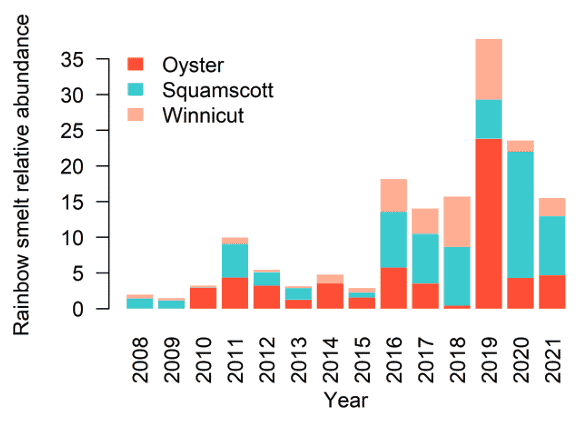

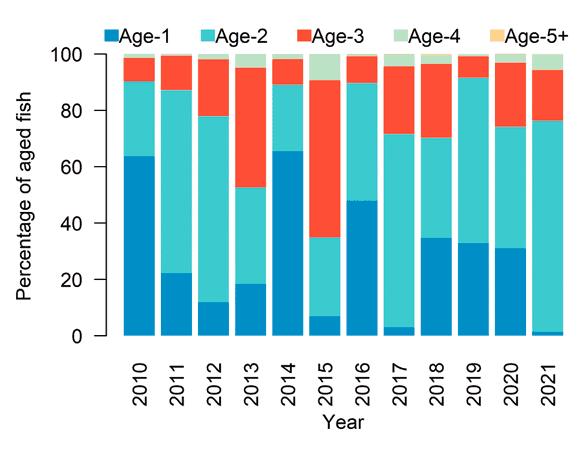

Rainbow smelt (Osmerus mordax) are also migratory and monitored by the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department (NHFG). Removal of head-of-tide dams on the Winnicut (completed in 2012) and Squamscott (2016) Rivers resulted in time-series highs in rainbow smelt catches within approximately three years after restoration of each respective river (Figure 20.3). Whereas rainbow smelt spawn in the Squamscott River, river herring continue upstream into the Exeter River, and they all share the same migratory pathway to the Great Bay. The catches of rainbow smelt on these rivers have continued to be considerably higher than they were during the time period before dam removal. In addition, in the most recent years, the catches are composed of a higher proportion of 2-year-old fish relative to 1-year-olds (Figure 20.4). There are many possible explanations for this, such as poor spawning effort or poor survival of juveniles. More data will be necessary to understand these dynamics.

Acknowledgments and Credit

Nathan B. Furey (UNH), with contributions from Kevin Sullivan (NHFG) and Robert Atwood (NHFG).